On Pretending

Alright, I need to admit something. When I'm in the middle of my very own, very best Rocky-training montage, I'm usually listening to a podcast. Yup, as I leap over benches and bust out pullups around Lake Merritt, I'm listening to Ira Glass' culturally androgynous mumble.

In fact, I think Ira and the entire NPR-fueled story-telling ethic is currently propping up the whole weight of storytelling and its central place in the arc of human history. Combined with the fact that, as my buddy Nathan likes to say*, information doesn't matter anymore--everything you could ever want to know is a thumb-spasm away on your smartphone--NPR's place of prominence is somewhat surprising.

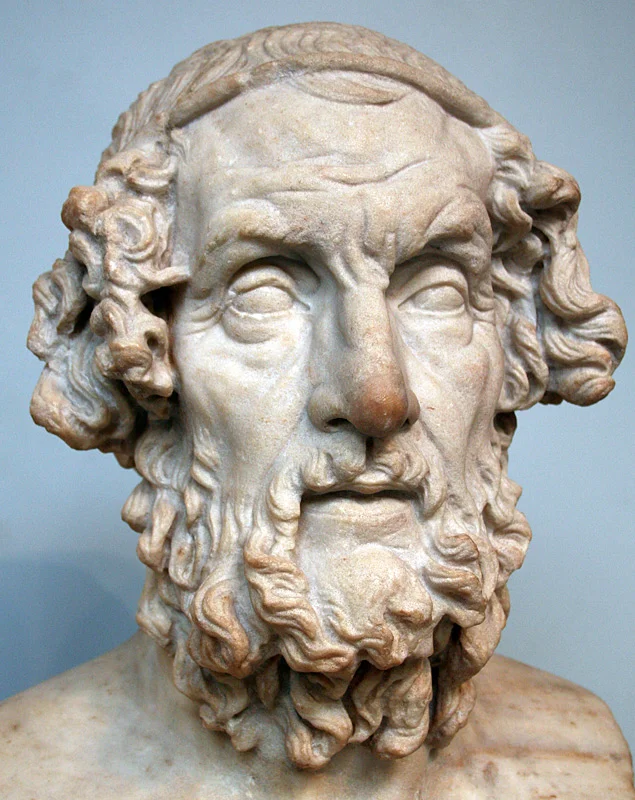

Considering that the oral tradition (we think) was our first system of societal-cultural crowd-sourced knowledge accumulation, it would seem that an oral tradition is really obsolete. And it definitely is! ...as an information bank. But importantly--and this is where NPR lives--the art of speaking about us, as genuinely and truthfully as possible. and in a way that invites the audience to personally engage, still matters. It still matters because it's one of those treasured places where morality comes from, and it still matters because it is the product of a whole lot of committed doing by the journalists.

Alright, now you know the depth of my love for NPR (I'm a f*ckin hippie, ok?!). And while quality goes up and down, a recent This American Life (TAL) episode hit me right in the chest. Maybe it was the recent changes in my life, or maybe it was how miserable my run felt that morning, but something about Episode 198: "How to Win Friends and Influence People" carved out a spot in my head and set-up shop. Here's what I heard it saying:

The hour starts with Ira interviewing director Paul Feig about what "influencing people", the implied key to "winning" and having "friends", really means. Apparently, it means manipulating interactions so that other people feel cared about, it means winning the election for student-council president in 6th grade, it means losing that presidency when everyone realizes you are a phony who just wants to win the popularity-contest. And, in the end, it means tuning in for the first time to the all-important language of implicit communication in human interaction.

The show then pivots to a David Sedaris story about the dark side of "winning friends and influencing people"--what it feels like to be at the bottom of the human dog pile that is middle school in America. After a popular kid, Thad, beats him up and causes enough damage to warrant a dentist bill, David's dad has a meeting with Thad and his parents. Thad says all the right things--David frantically agrees with him--and the situation is smoothed over. The enduring image is that of Sedaris "forever holding a place in his heart" for Thad, even if their only significant interaction was when Thad's fist made contact with David's jaw, in 7th grade. As I think about that one (Stockholm syndrome? Chronic apologizers?), I see present-day and grown-up David as the not-so-guilty victim of a ruthless social hierarchy. Eccentric, sure, but not exactly culpable.

At this point, TAL has laid out how it is for the winners (Paul Feig) and the losers (David Sedaris) in the arena of Social Influence, and I find myself pondering an alternative. Who can you possibly be, if not a "winner" or a "loser"?

What about those people who just pretend to be winners? Are they desperate optimists, the self-help gulping masses? If they're not actively engaging with the rise or fall of their personal status-star, are they of any use, to themselves or society at large?

Actually, and acutely, yes, I find out as I keep listening. The next journalist on TAL titles his story "People Like You If You Put a Lot of Time Into Your Appearance," and I expect to hear a comedy piece about how appearances don't matter and we'd all do better acting less like vain dipsh*ts. But instead, Luke Burbank recalls the time that he took a plane flight sitting in front of a guy dressed and acting authentically if not explicitly like (but also not not like!) Superman. Ah! a refreshing if sobering fiction piece, you think.

Wrong. This Superman character is a real dude who actively pursues an engrossing hobby as a costumed character, loose in the bars and restaurants of his small Washington town. When asked, he freely admits to not being Superman, and doesn't even really play up the "I'm Superman" schtick in his demeanor.

That is, except for one facet: his appearance. On that part, our humble Hero commits all his resources. Between hand-sewing costumes, working to be in great physical shape, even customizing his car, this guy has decided that his life is best spent pretending, in a passionate way, to be someone--something--else. In fact, he fully understands that the verisimilitude is essential to the power of his statement.

This guy, Mark, was initially inspired to his calling after his wife died a couple years earlier. Although he was a lifetime Superman collector, Mark's wife's passing pushed him to take his passion out to the greater public. It gave him a purpose and meaning, and a diversion, right when he needed it most.

These days, it's a self-sustaining pastime for him in that the reaction from his fans, new and old, is universally positive. It makes their lives better long after it had filled the hole in Mark's life. Making other peoples lives better in a way that also sustains you: can you ask for more than that in a life?

Yes, it is a performance, and no, it isn't real. Yes, it's frivolous and "wasteful", but no, it is not selfish. Yes, it enriches his community, and no, that enrichment doesn't come from trashing third-world countries or sustaining socio-economic prejudice. And it all came from a single actor deciding to commit. In the end, what he's committing to matters much less than the fact that he committed at all.

There was another bit of fluff to finish the program (a lush, fictional account by Lois Lane's rebound boyfriend after she dumps Superman), but the lesson had been made clear: the crucial tactic to overturning the Popular - Not Popular dialectic lies in the individual's willingness to risk complete annihilation, at his own hands, in the striving toward...something--anything.

So go do things, and do them with everything you've got.

--

*He usually says this right before I blow my top about the life-hack phenomenon ("You can't teach yourself mastery on the internet, bro!"), but that's for another blog post.